Industry experts are saying Apple’s new I-Pad is a revolutionary development in visual communication, able to deliver page and video formats wirelessly and in color to handheld devices not much bigger than a magazine.

At this point, who knows if the

I-Pad will change anything beyond its early market hype? Vertical applications for this new device are still a ways off, especially for construction managers who are still struggling to keep pace with all the other technical changes now flooding a very competitive industry.

In practice, some construction companies are only just now taking advantage of simple email and page publishing programs, including texting messages and photos from the field to wirelessly file daily reports on project activity. However, except for a handful of the more technically advanced companies, most of the industry remains reluctant to place graphical information systems of this kind at the center of their management methods. That takes time, money, and talent.

Technical advantages

At the same time, most construction organizations know from experience that competition for projects is going to get even more intense as the economy finally comes out of the starting gate.

That level of intense competition will mean finding ways to take advantage of tools and ideas that give the winners a competitive edge in a rapidly changing economic environment.

The Internet and websites like

Allan Spear Construction are obvious examples. Just a few years ago, the idea of investing in a web page was only a passing interest for most people in construction. Few saw the potential of the web to graphically clarify their mission, visually promote a strong company image, and illustrate unique proprietary processes that are often buried and forgotten in project proposals.

While most now accept that some online presence is a necessary business expense, the more innovative industry leaders have pushed their websites to communicate new management approaches and systems based on track records of real world experience. This means they’ve found ways to add depth to their market perception, increasing their lead over the more conventional construction companies even further.

In fact, the challenge of seeing and adapting to change makes this a pretty exciting time to be an innovative construction contractor. Constant and continuous change creates all kinds of opportunities for quick thinkers. It triggers shifts in the marketplace and seemingly insignificant openings that technically aggressive people and companies will be able to squeeze into in order to beat out the slower, late adapters. When that happens, the powers of these technical innovations will expand market expectations, setting the bar a little higher for everyone trying to maintain a competitive organization.

Visually Augmented

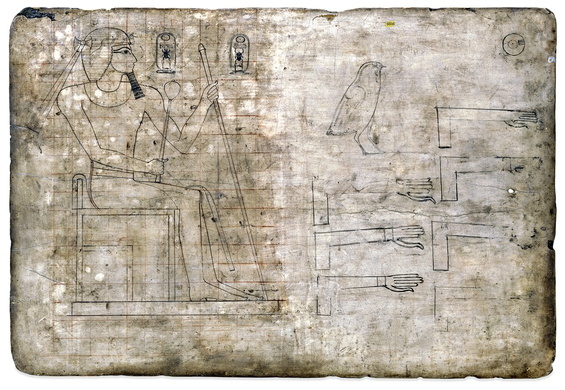

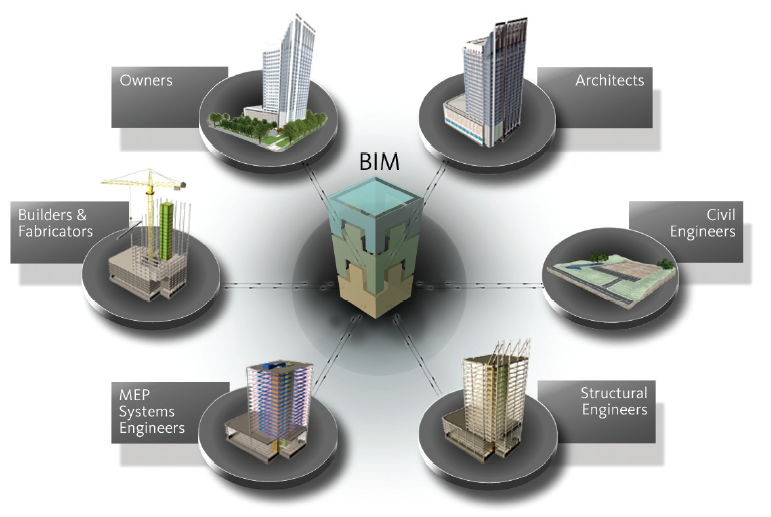

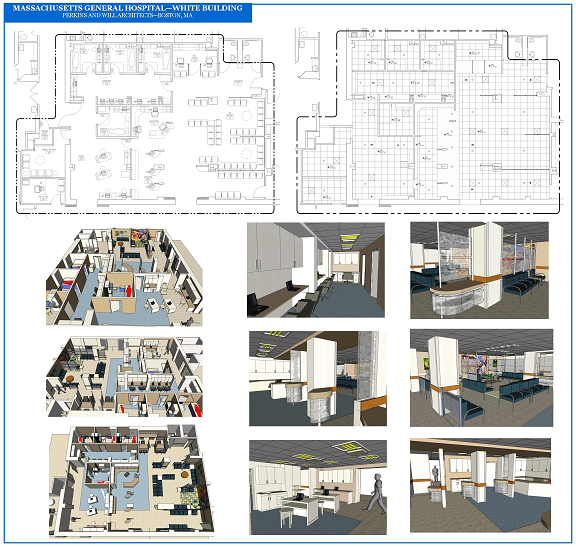

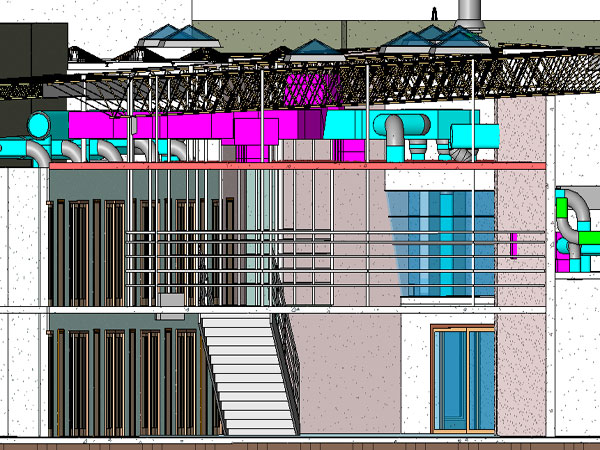

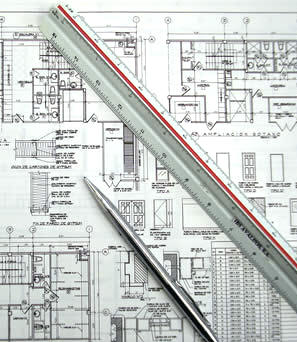

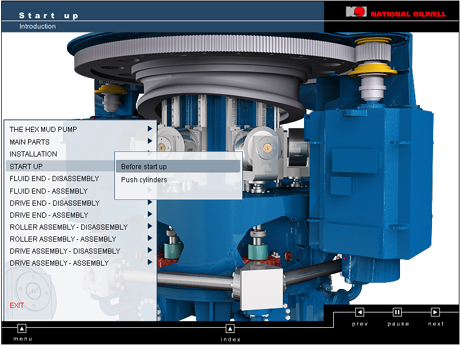

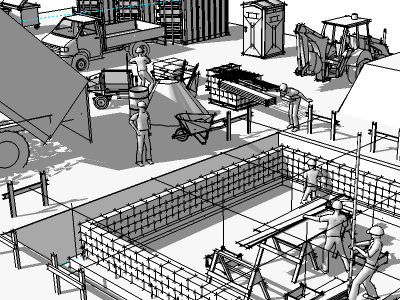

In today’s fast paced world of construction, it’s not about drafting or reading construction drawings any more. New graphical devices are becoming central to visual communication strategies that are far more powerful than drawings and words alone. These are descriptive images that open doors to an ongoing conversation where interactions and details evolve (or dissolve) over time.

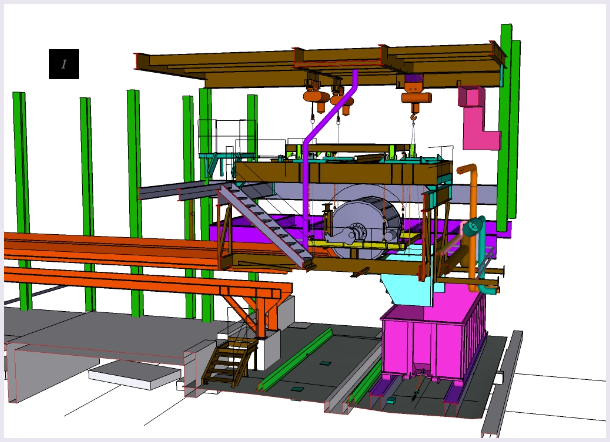

Important is that technology is not central to this exchange of information. It simply augments the experience and knowledge available to a generation that has never feared its implementation. What we find are construction managers who have either grown up with these tools, or had the imagination to recognize the potential of construction models, animated images, and graphical networks and how they can assist them in delivering a higher level of services than were once possible.

Also important is that these communication technologies are embedded in a mindset where these same construction managers are able to step away from their power and apply a personal, more face to face approach whenever necessary. These are professionals comfortable with visual explanations and able to use it to their advantage whenever it’s necessary. In other words, what may be complicated or difficult to others is no more than a simple set of tools that help them do their work more efficiently. Most interesting is that they join a network of similar thinkers across the broader project development community -- our clients.

What we see as a result is a technically augmented group of managers. These are primarily men and women who have not only adapted these tools to their social and professional lives, but internalized their potential as part of their innate competitive motivations. As such, they’re secure in using these strengths to market their services whenever it works to their advantage.

Layers of visual explanations

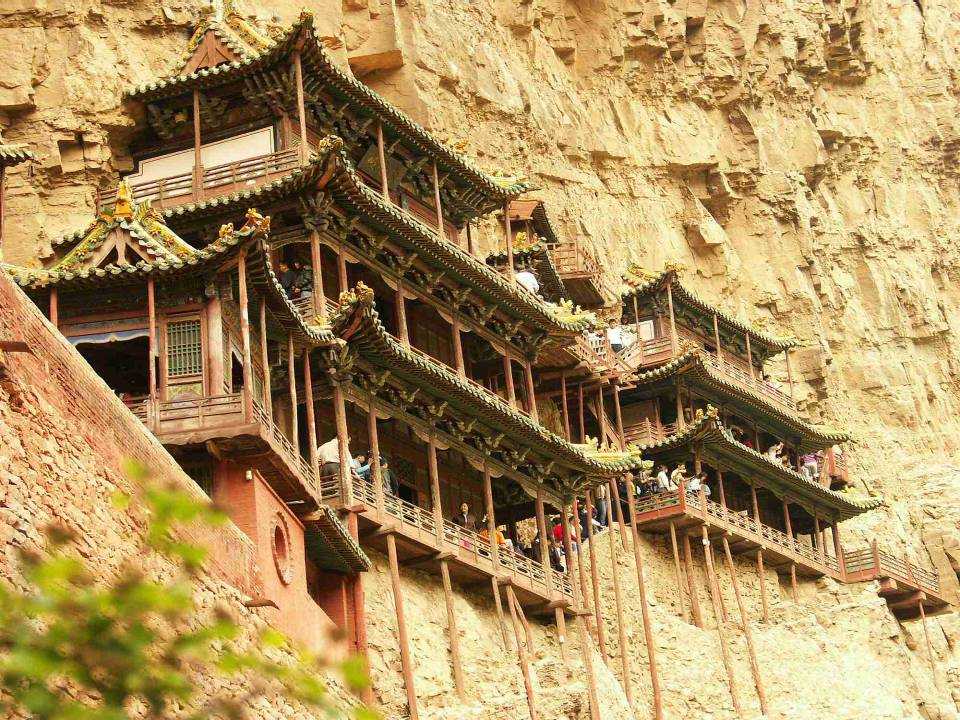

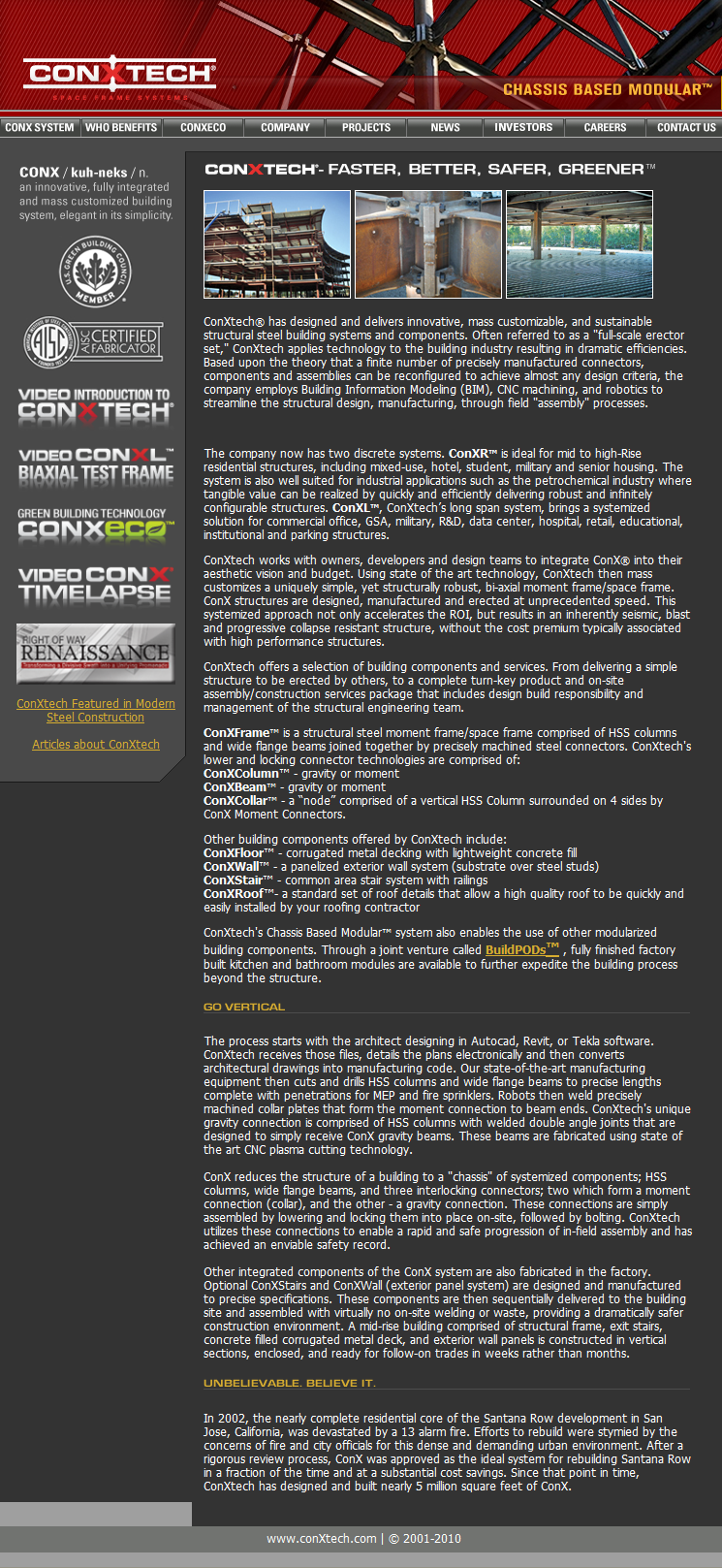

Technical augmentation like this is central to real world competition. Consider a truly assertive website like the one used by

ConXtech in Hayward CA. This site becomes an information delivery system, based on a layered visual presentation as an approach to both a revolutionary product and an innovative construction method.

On this site, graphical information mixes with video, animation, and interactive content that changes according to client interest, adjusting levels of supportive information, posted continually to the web for immediate review.

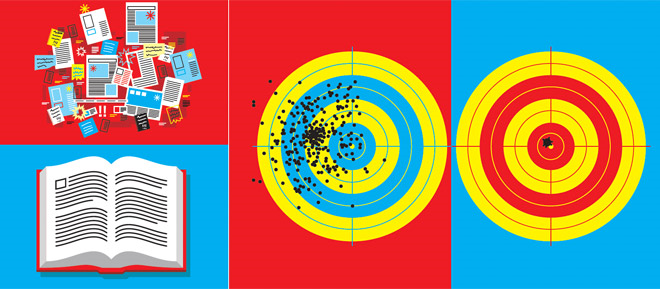

When an interactive presentation like this is seen next to a company showing a template of 20 or 30 canned Power Point slides, with a lot of the same old industry jargon, written tediously as text-based bullet points, it becomes obvious that old school thinking is struggling to remain relevant in a modern age. Dated companies like these are often far behind the curve and less able to keep pace and collaborate with a more technically proficient project team.

After all, it’s the construction industry’s development clients that are the first adapters of almost any system that improves investment potential. Otherwise they wouldn’t be in the project production business – at least not for long.

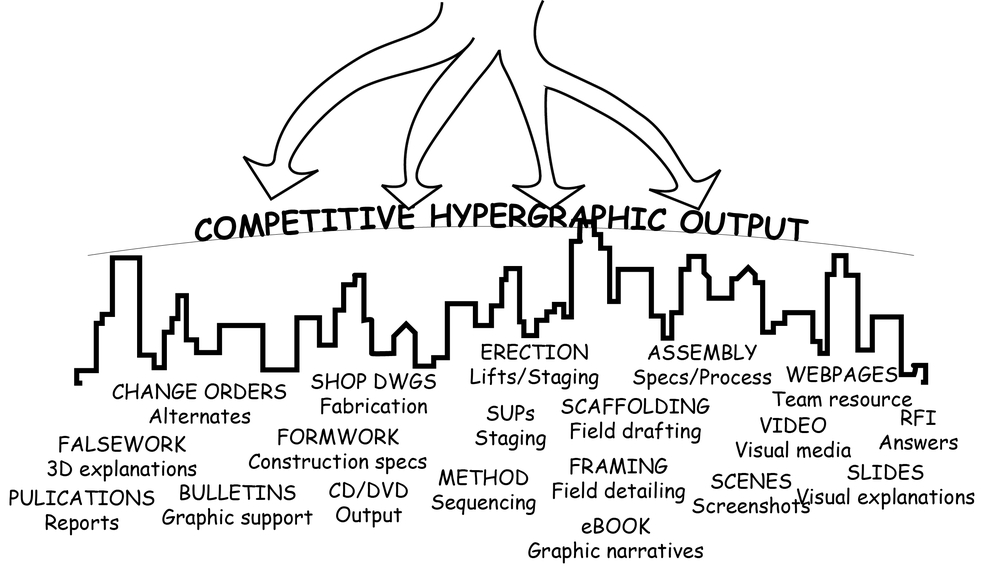

Turning toward hypergraphic communications

When fully incorporated into construction management, these graphical tools provide advantages that are fast becoming part of both social and professional interactions. These are tools that may seem disruptive to outmoded schools of thought, but are simply natural extensions of expression to those that are able to put these technologies to work.

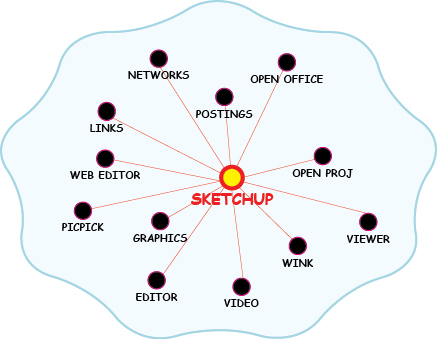

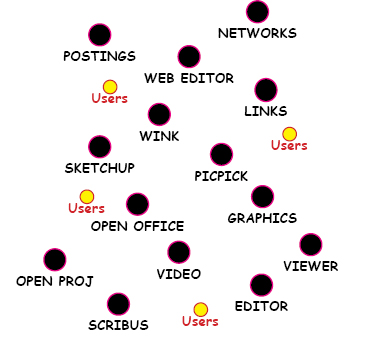

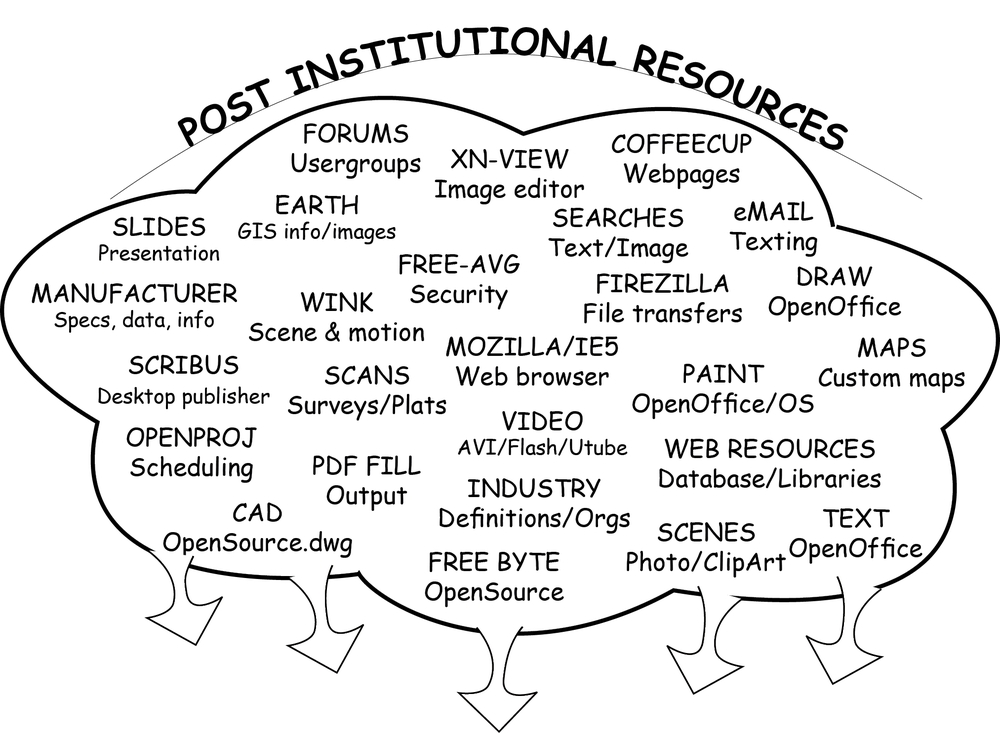

Most interesting is that each of the tools is open-sourced, user defined, and free from the constant need for upgrades that are required by expensive commercial software. Like any tool or piece of equipment, all they need to be effective is a little training, a bit of practice, and periodic maintenance.

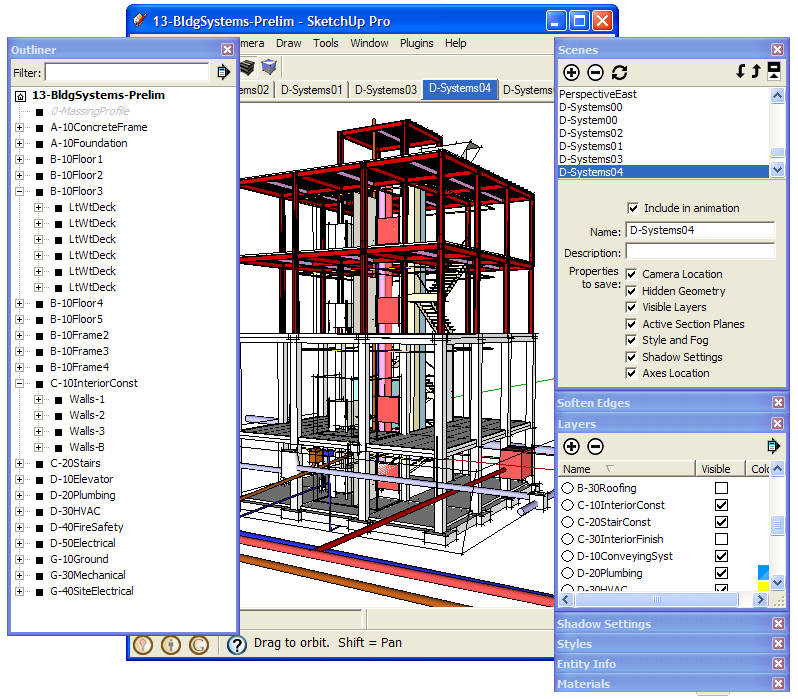

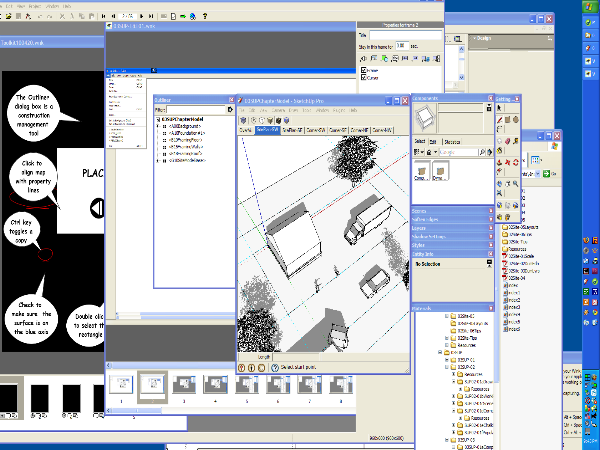

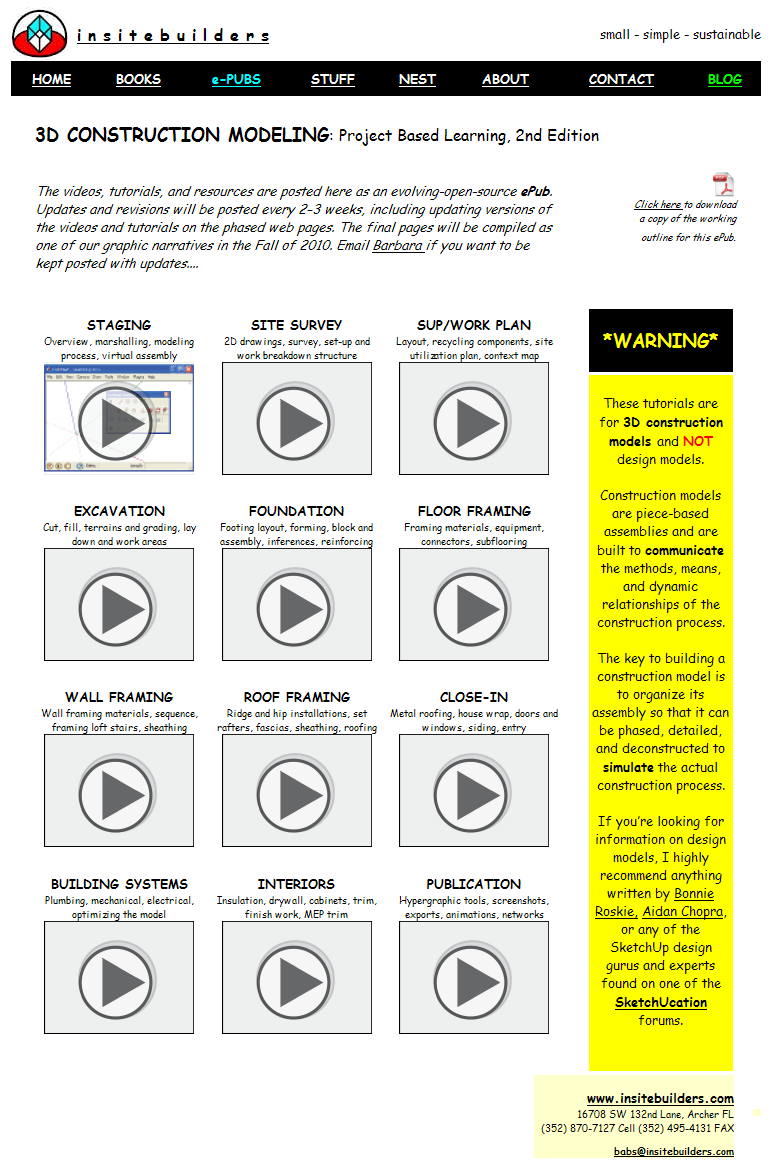

To demonstrate the potential of a variety of hypergraphic tools, we’ve begun posting a series of tips and tutorials on the ePub link of the

Insitebuilders website. The lessons linked to these pages are a work in progress and change daily, but you can follow along as we try different formats and software, demonstrating their potential for hypergraphic construction communication.

Our goal is to graphically empower constructors so they can begin to communicate their ideas throughout the project development process.

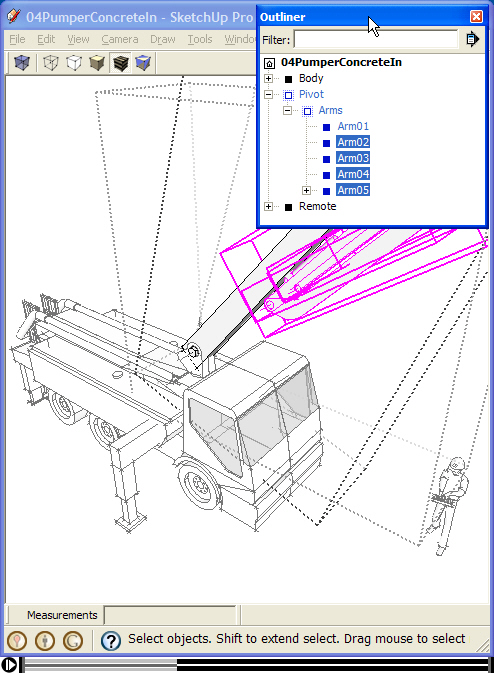

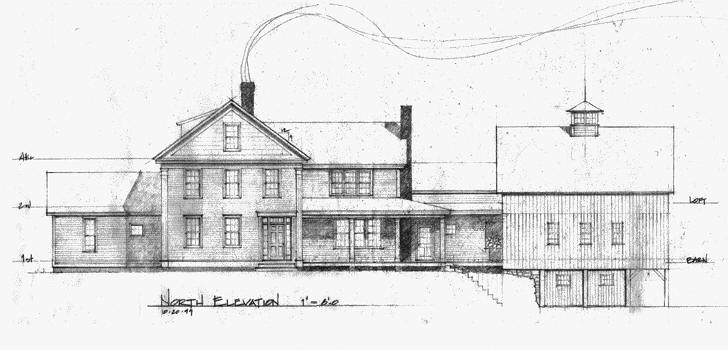

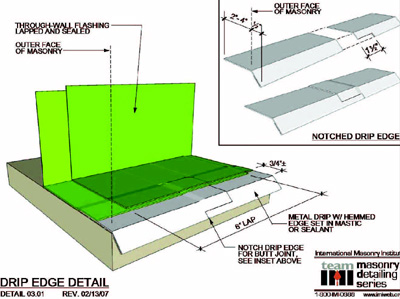

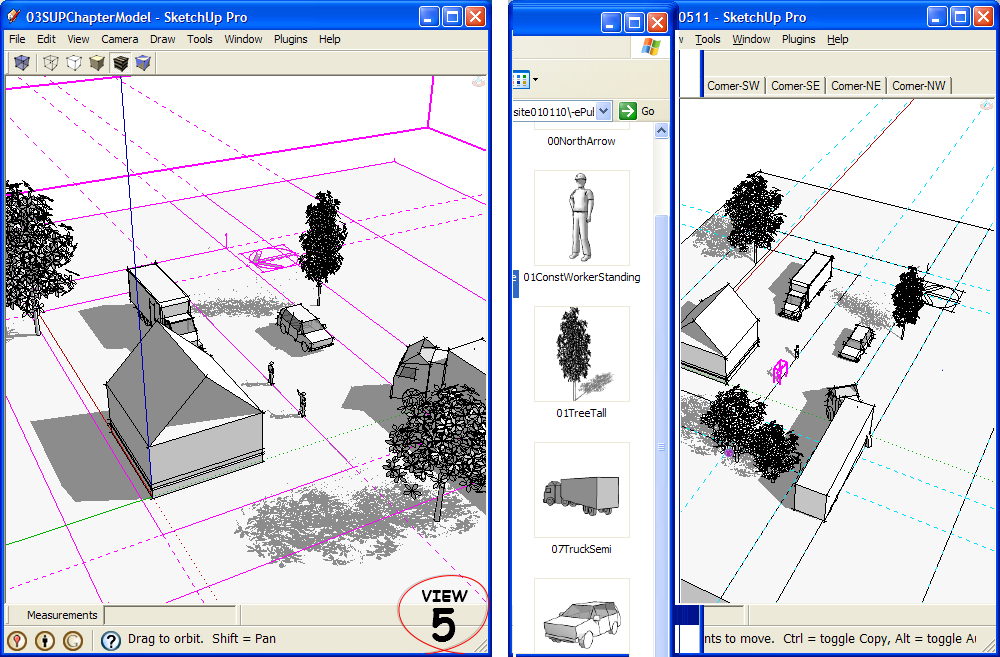

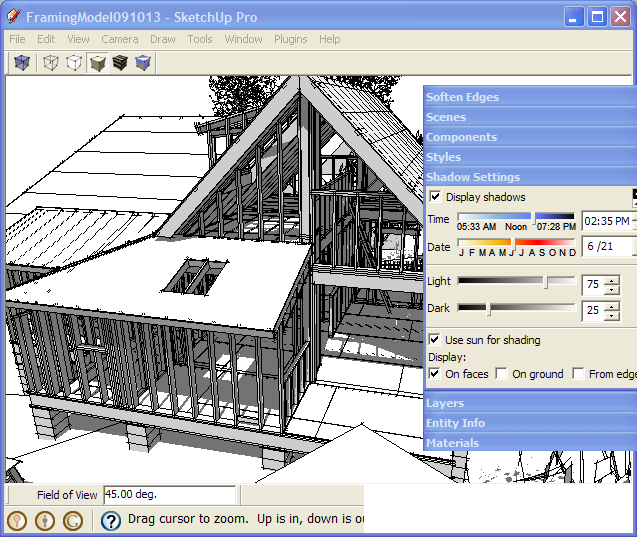

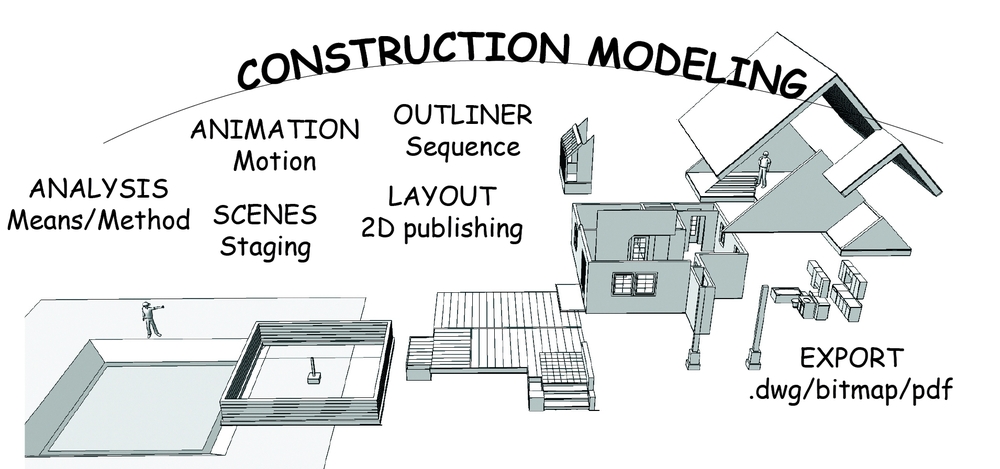

As you’ll see, visual explanations in construction are based on the ability to quickly build simple 3D models similar to those found in

our books. 3D construction models visually explain the means and methods of a particular process because they can be sequenced, annotated, and published to the web.

It’s the web, along with the I-Pad, that makes the potential of Apple’s new invention most worthy of note for the construction industry.