The idea that free and open source software might actually democratize construction communications could actually be a driving force behind the ongoing drive to upgrade CAD programs. Just to survive, software developers must constantly add layers of complexity to their products simply to create a marketable need for a competitive upgrade.

Of course, the percentages of system managers able to use or find consultants who can work with each newly marketed upgrade is limited at best. And the search for compatible collaborators only adds to the market perception that not owning the most actively promoted new software, makes it somehow difficult for a company to do what was once a straightforward matter of getting a building built.

The Fatal Flaw of CAD

For an example, just look at the “success” of the so-called BIM model. While most are still trying to figure it out, the market’s perception is clear: good parametric models self-generate error free 2D drawings, collaborative menu-selections seamlessly link design and construction, and the implied promise of faster and cheaper real-world production.

These features are not sold to individual practitioners, but to a broader industry of media professionals, conference organizers, and developers hungry for news of more effective communications between design and construction professionals.

Of course, the mounting complexity of these programs is their fatal flaw. After all, the plotted output of even a high end CAD program is still a printed set of two-dimensional documents. Everything else is what Edward Tuft calls “fluff.” And every experienced builder and designer knows a set of plans and specs is only a fraction of what it takes to actually coordinate the construction of a building.

Social Model of Communications

In Wired Magazine’s February cover story, Chris Anderson writes about a post-institutional model of an open supply chain where designers and builders gain almost unlimited access to a vast social network of information, products, and willing collaborators on the Internet.

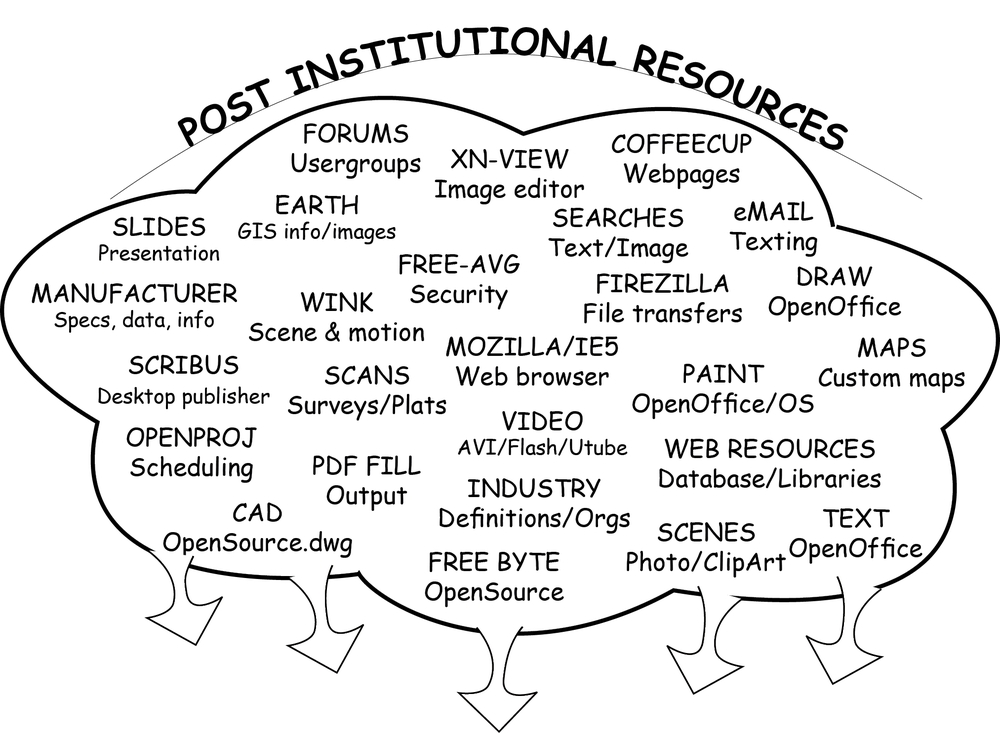

For our industry, this includes a variety of software programs that work easily together across a range of real-world applications. Ironically, these programs are not difficult to find and put together, but remain largely unknown primarily because no one is promoting them as a single software platform. When something is free, there is nothing to “sell.”

Post-institutional software also means upgrades are driven directly by the users of the product and not by a manipulated market of need. This mean the people using the software shape and share the direction of its development, sometimes in the form of faster or more efficient code, other times as plug-ins or add-ons written for some practical purpose, customized for a specific user group.

SketchUp is a good example of this kind of social development. Not because of the guiding hand of Google Inc, but precisely because of it’s almost complete neglect. Instead, Google leaves SketchUp open to a number of highly proficient, completely independent, Ruby programmers who seem to be able to make the software do anything an industry of users needs to put the program into practice.

And when plug-ins and fixes are not possible, an active user forum publicly pressures a relative handful of Google employees to correct problems and make the changes. Add to this community of interest, master modelers and use-group coordinators like those found at http://SketchUcation.com and one sees the essence of what Anderson means by a post-institutional social model on the web.

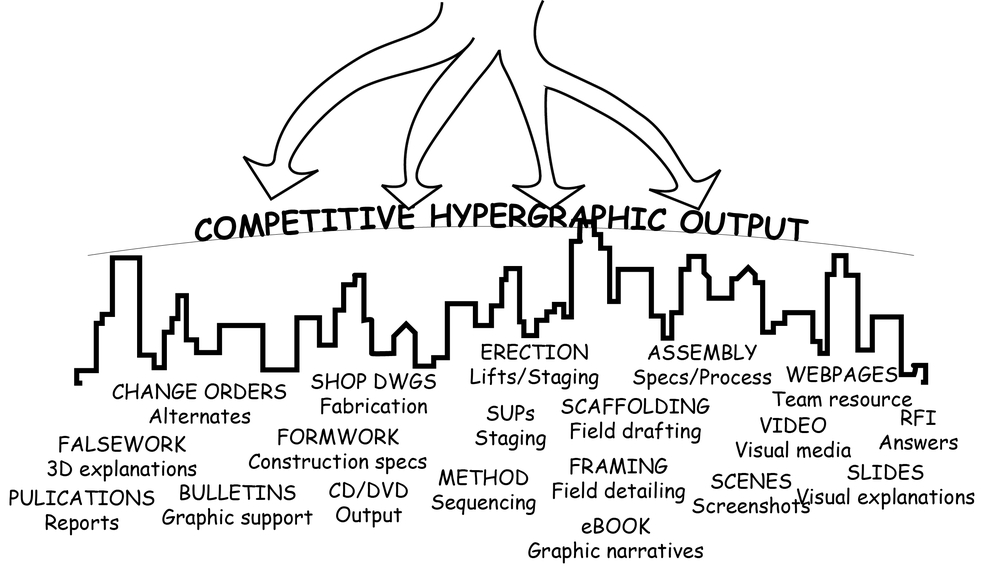

Hypergraphic construction communications

Software like SketchUp sets the stage for the kind of hypergraphic communications found in this social model. Hypergraphics is a synthesis of text and visual media, part of a critical method of thinking developed in the 1950s. The idea is that communication is multiform, intended to transfer a body of information in a variety of media, sometimes working independently toward the same intent or description, but just as easily varied and seemingly disfunctional.

The key to success in this post-institutional standard is to know what tools to collect from the web and how best to integrate their applications in daily practice. Much of this integration has already begun. Email, web research, and even CAD would not exist without the Internet and our current dependence on these new digital forms of communications.

In the same way, cameras are routinely found on jobsites, with pictures and video readily attached to communications and clarifications. Digital scans can now be posted or emailed directly from high speed copiers, including high resolution settings that capture every detail of a construction. And drawings, either sketched by hand on a piece of drywall or drafted on a machine, remain at the core of construction communications, more often than not, copied into the project records as part of a database of archived construction information.

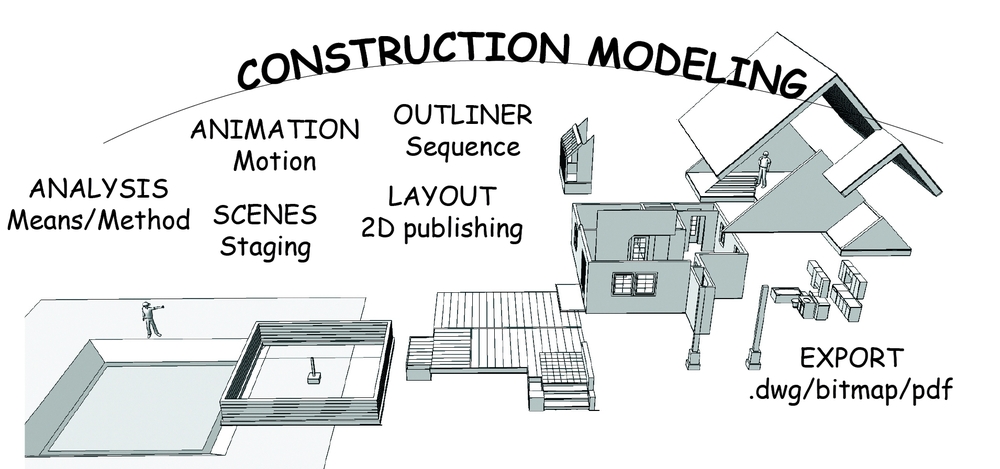

Capturing Sequence, Scene, and Motion

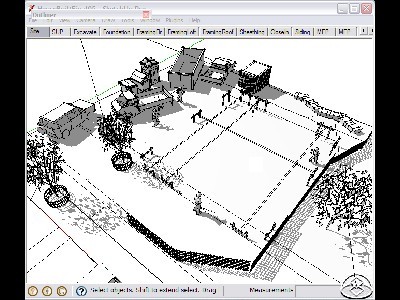

One thing is clear, quick and simple construction modeling is at the heart of the tools necessary to communicate effectively in an open-source post-institutional environment. When 3D construction models are quickly generated in the field, their output facilitates three-dimensional explanations of what has all too often been found buried in layers of two-dimensional scrawl on wrinkled sheets of rain stained paper.

Instead, images extracted from a construction model set the stage for capturing the sequence, scenes, and motions of the construction industry. Sequence is assembly and action. Scenes are events and milestones. And motion displays both means and method over a given time.

What we demonstrate in all of our books is the fact that when these tools work together, they join a hypergraphic narrative as a pattern of multi-media messages. These are cross platform approaches using quick and simple, good enough programs, that serve to communicate exactly the kind of real-time information necessary to get the building built.

A Small Home of Your Own: Plan Permit Pay in 3D