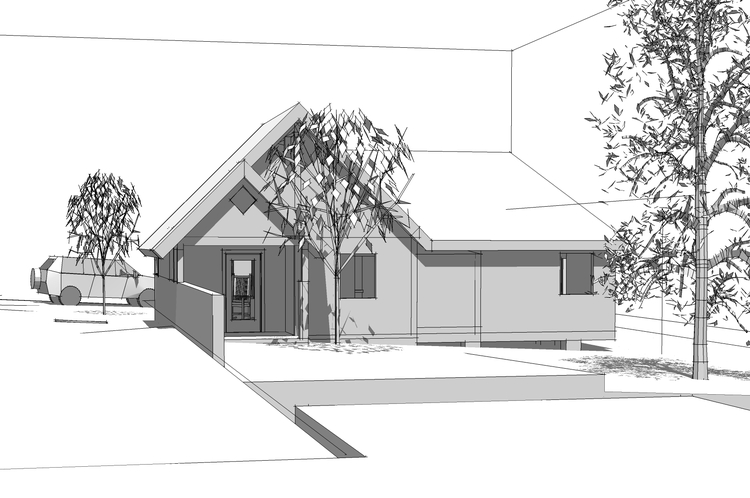

The Preliminaries are a set of scaled plans, elevations, and sections – refined from conceptual sketches and schematics – that become the first drawings in a set of construction documents. These construction documents include details and specifications that become attachments to a legally binding contract and the basis of the building permit authorizing construction. In other words, the documents are drawn for lenders, attorneys, and code officials.

These drawings are drafted to a scale and format required by local building officials so that they can be referenced in a series of site inspections leading to a Certificate of Occupancy (CO). The CO is necessary to register the building as legal property, close loan agreements, and transfer the project as property to the local tax rolls.

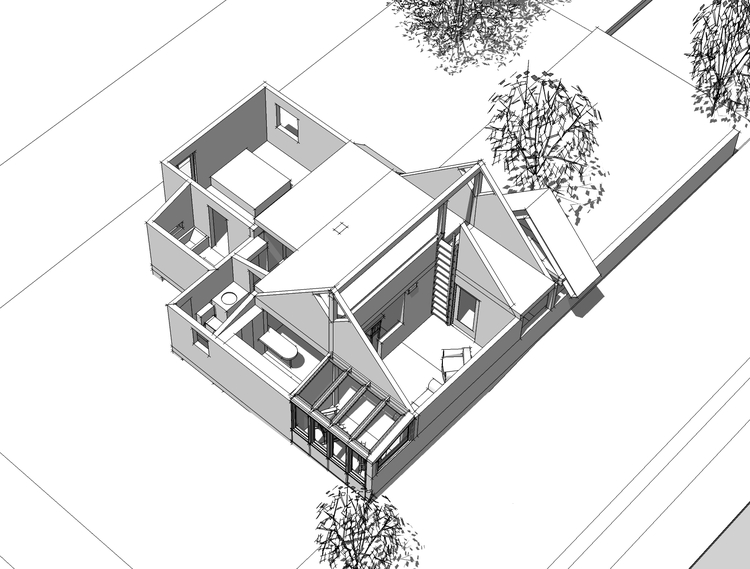

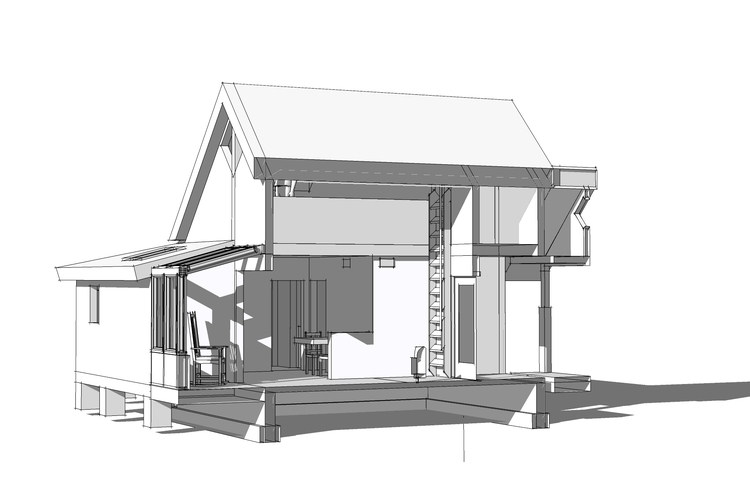

The challenge for designers and builders on both sides of these contract documents is that a multidimensional process must be reduced to a collection of two-dimensional diagrams, symbols, signs, and notes. This limits the designer’s ability to suggest operational details for the construction and forces builders to translate abstract images into actions that are much more involved than two or even three-dimensional interpretations.

It’s not rocket science

Shape and form may have a place for some, but what’s most important to a builder is process. In construction, process is “means and method.” It’s how a particular builder intends to actually put the building together and what makes one builder more competitive than another.

What’s important here is that seasoned builders can estimate the cost of construction by simply looking at the Preliminaries without carefully thinking through either means or method. To do this, builders apply a rule of thumb, or unit cost based on current market conditions and their own experience with similar buildings. If there’s anything unusual they simply adjust their prices intuitively.

Estimating by unit cost is only possible because every trade on the project uses their own rule of thumb. Carpenters and finish workers count square footages, masons yards, cabinet makers linear feet, plumbers fixtures, and electricians count outlets.

This seemingly relaxed approach to estimating the cost of construction follows a time not long ago when builders worked without the formalities of plans and specifications. Castles were built from oil paintings, high-rises from inked linen, and builders as designers were confident that they could figure things out as they went along. Today of course, this openended approach sets the stage for trial and error, conflicts and conditions, and corresponding cost overruns and delays.

But the point is that the cost of construction can be determined from the Preliminaries without carefully considering either means or method because the details, notes, and specifications in the contract documents for most buildings follow standard practices. That’s why CAD files, boiler plates, and sticky-backs can be cut and pasted from one set of drawings to another. Construction is not rocket science.

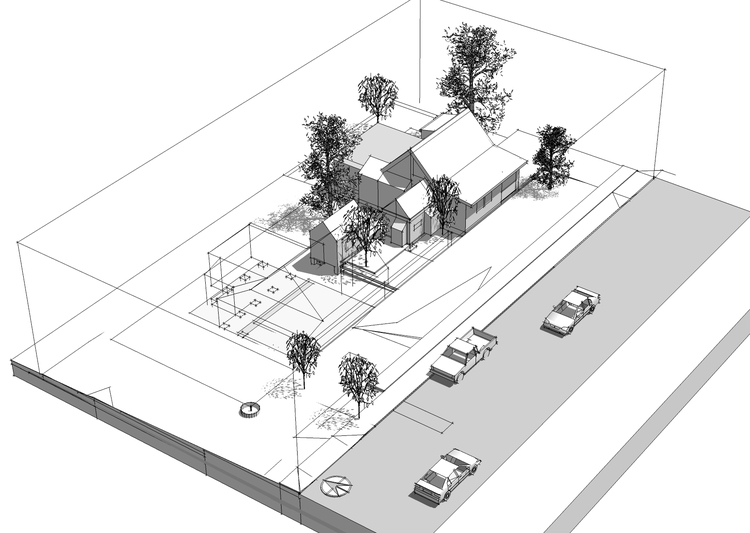

Self-evident simulations

What you’ll see in this house then is not that its construction is so difficult, but that it’s so far removed from the norm. I designed the house to combine a number of different construction practices. This includes a variety of field conditions that are similar on many projects – residential or commercial, wood or steel, but the building itself is atypical and would be a challenge for most builders to build.

Because the process drifts so far from previous experience, it enters unfamiliar territory for each of the trades involved in its construction, requiring additional management and attention that cannot be easily broken down into a unit cost.

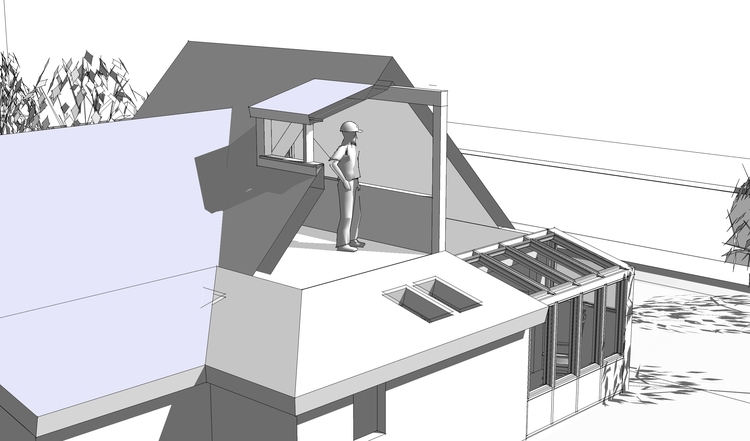

What’s interesting is that a quick glance at the illustrations shown here are also sufficient for us to start a virtual construction once a few dimensions are clarified in the field (next article). What this means is that process can be simulated when we think through the assembly of this house in a piece-based construction model in almost the same way it was once done by early masterbuilders.

As such, construction models suggest an interactive document that might better serve builders working with the variables of the real world. What such a document might look like as a contract remains to be discovered, but the idea of using multidimensional programs like SketchUp to represent each step in the construction of a building is exactly the point of this series of articles.

---------------------------

The material presented in this series has been taken from our book, “How a House is Built: With 3D Construction Models” The book includes annotated illustrations, captioned text, videos, models, and the 2D Preliminaries.

(To be continued…)

.